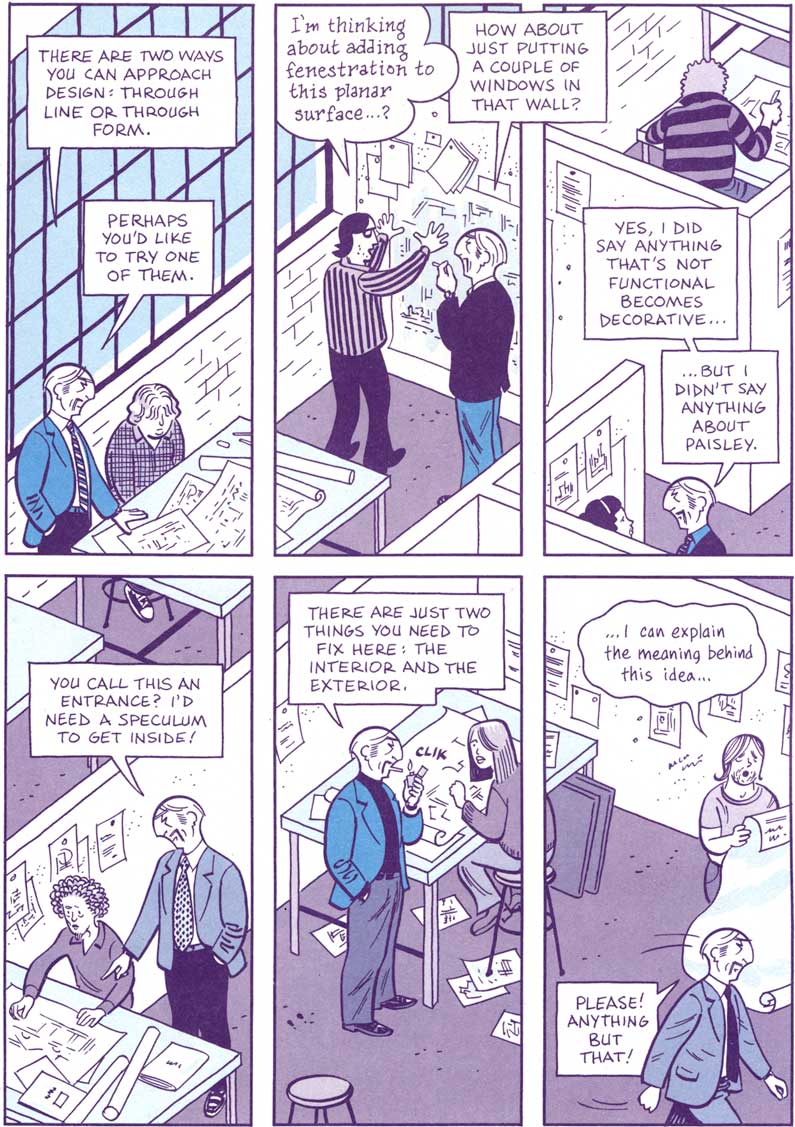

Early in David Mazzucchelli’s graphic novel Asterios Polyp, there is a page with a grid of six panels which, viewed as a unified whole, shows a warehouse office space, filled with zig-zagging partitions; students sit at desks or stand before walls, sheets of marked-up drafts paper before them. The main character proceeds to walk through those panels, in each one firing off acerbic comments directed at his architecture students — “You call this an entrance? I’d need a speculum to get inside!” — until his angry verbal momentum carries him right off the page. It seems like a brief moment is captured here, except that Asterios, the professor, is shown in different outfits in every panel, an immediate visual indication that there is not only a progression through the physical space of the office going on here, but a progression through time as well. This is a portrait of what happens over several days, months, or even years, compressed into one terse page of carefully constructed word and graphic.

At this point, those who have followed the career of Alan Moore might be reminded of a singular page that has gained legendary status amongst his readers. It is from a never-completed, experimental series called Big Numbers, a series that seemed to promise — in the comic book medium’s heady mid-1980s, when a flux of reinvention and unprecedented maturity was underway in its mainstream — a permanent breaking of the already-crumbling barriers of convention. Big Numbers was about a massive American mall being built in a small British town and how that affected the community — its everyday reality, its economics, its overall life. The work was written at the time when fractal geometry was in the news, largely due to the success of James Gleick’s bestseller Chaos. That philosophically fertile branch of mathematics had inspired both the name of the series and its approach, that of finding unexpected order in the seemingly disconnected flux of daily existence. And the series itself, projected to be twelve issues, would fully embrace complexity: it was to be relentlessly ambitious and post-superhero in every possible way.

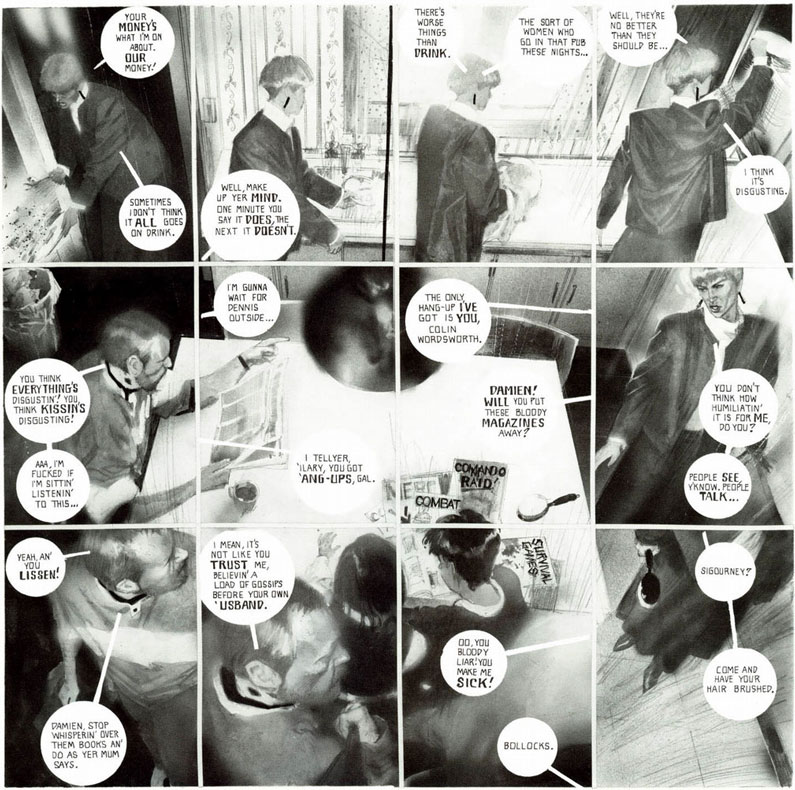

In its second and last published issue, bravura artist Bill Sienkiewicz, who combined disparate styles in the square book — shifting between black-and-white painting and various illustrative pen-and-ink techniques — drew a page with 12 same-size panels depicting a husband and wife arguing across a kitchen table as their two children silently shuffle through comic books. As the argument continues, the woman walks around the table and the man gets up and departs. The carefully choreographed and complicated dance of conversation bubbles and visuals is a marvel to look at: one is compelled to stop and take it in again so that it can be fully appreciated. An innovative page and an indelible image, it speaks iconically of the wide gamut of possibilities waiting to be set in motion in the comic book industry, once it fully and finally transcended the adolescent superhero mythos.

In many ways, Mazzucchelli in 2009’s Asterios Polyp realizes much of what Moore and Sienkiewicz had attempted to do in 1990 with Big Numbers: tell an ambitious real world story of philosophical or sociological depth, and do so utilizing an array of graphic and narrative techniques unique to the comic book medium.1

This isn’t an accident. Moore (a British writer) and Mazzucchelli (an American artist) were both in the middle of the mainstream comic book reinvention — in technique, maturity of content, and publishing materials — of the mid-1980s. (Mazzucchelli worked with the legendary writer/artist Frank Miller on a seminal re-telling of Batman’s origin story at the same time that Moore built his unassailable reputation in American comics as the writer of Watchmen). A shock-of-the-new paradigm shift occurred in the comics industry then that may be hard to explain to the uninitiated. A useful analogy might be to think of the shift in the television sitcom landscape in the wake of the neurotic greatness of Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David’s creations; or what David Chase did to revolutionize television drama with the no-holds-barred reality of The Sopranos. The medium had entered a new era. After those mid-1980s works (The Dark Knight, Maus, Watchmen, to name the oft-cited exemplars), the comic book was suddenly a new beast. What preceded those pieces had charm and vigor, but no real daring or maturity; what followed them had to live (or cower) in their shadows.

Alan Moore arguably remains the stand-out figure, intellectually and artistically, in that modern-day phase of dynamic reinvention. Gary Spender Millidge, in the synoptically-titled and lavishly illustrated Alan Moore Storyteller, attempts a comprehensive survey of everything Moore has done since the day he stopped working as an office clerk at a gas company (when he was 24, in 1977) and took the risky decision to build a career in comic books, first as a fledgling artist, and then as a writer.

In the early days, he built a solid reputation crafting short pieces for the British anthologies Warrior and 2000 A.D., which led to series work on Captain Britain, Marvelman (re-named Miracleman for U.S. publication) and his own creations, V for Vendetta and The Ballad of Halo Jones. Only a few years later, he accepted the job as writer for DC Comics’ Swamp Thing, which he proceeded to re-invent and re-invigorate, before turning to the extraordinary Watchmen, illustrated in workman-like grids of perfect comic book art by illustrator Dave Gibbons. That work, a multi-faceted jewel wrapped around the paranoia of nuclear war and concerned with the lives of people who donned superhero costumes in an attempt to make a better world, became iconic: the comic book series in which "superheroes" engaged in real-world problems and issues, and were potentially shattered by them. In 2005, Time named it one of the best English-language novels published since 1923.

After that, ambitious projects (Big Numbers, From Hell and Lost Girls) were conceived and Moore moved away from the larger publishers towards the independent comics market and self-publishing. This difficult path was inevitable: the industry’s attempts at self-regulation of “mature” material, and repeated battles over character ownership and publishing rights, created conflicts Moore abhorred, some bleeding into his relationships with fellow writers and artists. He attempted to move beyond these incessant business entanglements, but it was a tricky matter. The failure to complete Big Numbers, self-published under his own imprint, was in many ways a casualty of this transition. (The soaring ambition of the work, along with complicated personal factors, also contributed to its downfall.)2

But slowly and surely, Moore carved out the next phase of his career. From Hell (an analysis of the ideas and culture of Victorian England, using the Ripper murders as a guide) and Lost Girls (an experiment in literate pornography) would be shunted between publishers, but eventually finished and critically hailed. He would go on to create The League of Extraordinary Gentleman, an invigorating, multi-referential, pulp-action mash-up of Victorian-era fictional characters. It continues to be a fertile landscape for imaginative exploration. In a line of comics he created with a range of artists in the late 1990s came anthologies and comic book series like Tom Strong (a part-retro, part-new take on the brawny superhero concept), Top Ten (a super-powered police procedural) and Promethea (an exploration of magic’s connections with consciousness and creativity, with varied and scrupulously detailed artwork by J.H. Williams III and his talented collaborators). He did several unique spoken-word performances, produced an underground magazine, and is finishing a 2nd novel, Jerusalem, which is expected to clock in at a biblically long 750,000 words. Moore has quipped: “I just hope everybody will confuse quantity with quality.”

During this last phase, Hollywood film adaptations (most of them mediocre at best) of a number of Moore’s works were produced. This created additional unwanted conflicts for him with corporate entities, who, after realizing he didn’t want to be involved in any real way, still wanted his tacit approval of such projects (mainly for PR purposes). Moore wasn’t interested in providing such approval. In a comment that must have rattled the film company, he said in an interview shortly before the release of the Watchmen film (which was embroiled in legal rights issues, potentially preventing its release) that he would “be spitting venom all over it for months to come.” This ended up being nothing more than colorful rhetoric, as Moore largely kept quiet about the movie, expressing his disinterest in the project by refusing any money related to the film rights and by not allowing his name to be used in the credits. Those moves capped Moore’s relationship to Hollywood, which has charted a path from the fractious to the non-existent.

Millidge’s book covers all of this, and much else, in circumspect fashion, with select biographical details and summary insights from Moore along the way. Included are photographs of the writer from his childhood onward, reproductions of early work from his teen years, some behind-the-scenes sketches and planning documents for his major work — including a massive grid outlining the proposed plot and character developments for every issue of Big Numbers — and numerous comic book pages from the last three decades. It’s a thorough and enjoyable retrospective.

This is Millidge’s second book on the artist. Previously, in 2003, when Moore turned 50 and announced his departure from mainstream comics, he co-edited Alan Moore: Portrait of An Extraordinary Gentleman, a wide-ranging tribute featuring text pieces, strips and illustrations by artists and writers inside and outside of comics. In the same year (and updated since then) came George Khoury’s The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, a series of long interviews that has the advantage of utilizing Moore’s voice — articulate, honest, always humorous — to tell the story of his career, along with digressions on various issues of culture and politics. And since then there have been additional interview books, a one hour documentary, and even some of Moore’s notoriously detailed comic book scripts have been published.

That range of contextual material, unusual for an artist whose primary field is comic books, is partially a testament to the growing interest in the pop-culture character of “Alan Moore” over the years, which has been helped considerably (beyond Hollywood’s thrusting him into a spotlight he immediately evaded) by two overarching factors: the transformative effect he has had on the maturation of the comics medium, and the image of the reclusive, bearded sage, immersed in magic (and maybe madness) who now and then fires off barbed comments about the comic book and movie industries from the comfort of his Northampton home. Such a portrait is partially a myth, but an engaging one, with many admirers feeding its propagation.

But it is the work itself, in its emotional resonance and populist vigor, that has continued to speak to Alan Moore’s readers for the last 30 years. In that time, by way of a dizzying level of productivity — mostly in the medium he loved as a child and re-made as an adult — he has produced a gloriously varied mass of work, the length and breadth of which can seem daunting. But, for those who have followed him along the way, it all shades together and seems of a piece: Moore’s work circulates primarily around political anarchism, the joy of pulp action, love and sex, the darkness of man at his worst, the exploration of wider consciousness (largely in the terms of magic and creativity), and the complex possibilities for what we are as human beings in the world.

And his ambition hasn’t flagged. Jerusalem, the long novel he has been working on for some time now, is partially about “disproving the existence of death.” As Moore said to the New Statesman in 2011, “I thought that seemed a substantial project for my declining years.”

1. Asterios Polyp went on to win multiple comic book industry awards, along with the L.A. Times Book Prize in the Graphic Novel category (2010). The judges for the L.A. Times called the book a “beautifully executed love story, a smart and playful treatise on aesthetics” and “a perfectly unified work.” ↩

2. Twenty years after the two published issues of Big Numbers appeared, a remnant from the ill-fated project surfaced online: the rough pencils for the entire third issue. And in 2011, Bill Sienkiewicz provided his view on the project’s demise. As part of his commentary, he notes: “Alan’s a genius, an absolute gentleman. Plain and simple. Yes, his scripts are dense. They’re brilliant, layered, nuanced, variegated, textural, beautiful and daunting.” ↩