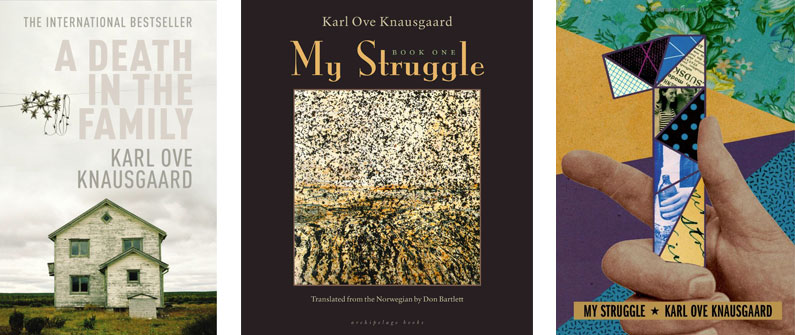

In an article in The Guardian in 2012 about Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic, 6-volume series My Struggle (“a scorchingly honest, unflinchingly frank, hyperreal memoir of the life of one man and his family”), Knausgaard is asked if he should have written the books, given the ruptures and chaos it has caused in his family life.

If I had known then what I know now, then no, definitely no, I wouldn’t dare. But I’m glad I did. And I couldn’t have done it any other way. I will never do anything like this again, though, for sure. I have given away my soul, in a way.

This revealing of one’s deepest self in the form of “fiction” is also the fundamental basis of Sheila Heti’s recent How Should A Person Be? The cover copy describes it as a “novel from life,” with words from Miranda July under the image of a vanity mirror: “A book that risks everything.” What kind of risk is this? What is reflected back when we peer at ourselves and how does that same life appear when reflected back to readers? In the end, does a crafted presentation of all the messy details of life — its personal idiosyncrasies, its humiliations, its mysterious ups-and-downs — coalesce into art?

Something of the basis of this kind of writing can perhaps be understood in comments Heti made during a podcast in 2011, while discussing her book with Misha Glouberman, The Chairs Are Where The People Go. In providing a context for the kind of writing she was interested in, Heti references Otto Rank’s book Art and Artists, in which Rank

was saying that in the future (which I take to be now) there won’t be any art, just artists. And the reason [for that] is because the problem for the modern artist is that they live their lives to get material, and then they go back into their studio and they make their art. But when they are making their art, there’s the loss of the experience of life, and when they are out in the world making life, there is the loss of [the experience of] making art. And so somehow that has to be resolved. The way that is going to be resolved, there is going to be no art. There’s just going to be artists.

Perhaps My Struggle needs to be approached in this kind of paradoxical way; that is, as literary writing that is immersed in, and somehow identified with, the texture of reality’s elusive “narrative,” the story of life that we can’t quite seem to grasp while living it. Perhaps one way to try to grasp it, to take hold of it, is to set it down in words — simply, frankly and without shame. Is this what Knausgaard is after? And Heti? Is “literary” creativity, in this sense, simply the stuff of the every day, slightly refracted and re-formed through the conceit of fiction?

I say perhaps because I have consciously avoided reading too much about the book before delving into it.1 I have only read enough to make these introductory remarks, as I want to approach My Struggle the way one should be able to approach any modern work of fiction: as a book that should stand on its own, artistically and narratively. I want to approach it spoiler-free. I look forward to finding out just what the book is, and where it takes me, and I hope others do as well.

This is where the social-read concept enters the picture. It is a unique way to approach a book, allowing readers to share their thoughts and reactions to the work as they read it. In doing so, we can see if our understanding of the work ultimately lines up, or instead diverges in interesting ways. It is something I’ve tried once before (in an LA Review of Books read of William Gaddis’s JR) and it was an illuminating and enjoyable experience, adding a dynamic, social context to the work that ultimately amplified its value.2 I hope the same is the case here.

Here’s how it works:

Starting on September 1st, we will read about 10 pages a day of My Struggle, Book 1. The relatively slow pace allows for the book to be read without disrupting other reading, work (or life!). One can fall behind and catch up fairly easily as well. As we read, we can freely comment on the book via Twitter, App.net, personal blogs, or wherever else seems appropriate, linking our comments to the hashtag #Struggle1.

I will be using the e-book edition of My Struggle, which is 393 pages long. (The current softcover edition is listed at 448 pages). Reading about 10 pages a day, here is where we will be in two week increments:

My Struggle opens, boldly, with death, and then closes with it. At first, it is presented as matter-of-fact, even clinical, and then left aside for a hundred pages or so. When it returns, it is all that there is. Its power over the living is spectral, subterranean and ever-present. To the conscious mind, it is a darkness virtually inconceivable.

From that darkness come emotions and memories unbidden. They deposit us in the past, force us to see ourselves as we were, and attempt to define who we have become. One’s existence can be a struggle to maintain a sense of choice and will in the face of life laid bare by raw memory. We wonder how the choices of others have refracted the paths of our lives, pushing us into places that we never intended to go. We fight against that, and yet accept it at the same time. We must. The mystery of the self — its freedom, its constraints, the complex trajectory of its formation — is fundamental and inescapable.

These are the kind of considerations wrought by Karl Ove Knausgaard in volume 1 of his six-part series, the “epic” story of his life and his family. We are placed in a world, this world, and shown everything — the houses that mark familiar points; the streets one walks down; the people that move in and out of one’s life; events that bring frustration or happiness. Experience is a ceaseless accumulation of ordinary facts.

And yet, here and there, reflectiveness follows and personal interpretation (sociological, psychological and philosophical) offers a modicum of overarching wisdom to the bits and pieces of monotony that form our daily lives. The banal can sometimes be followed by the profound, and the latter is a kind of elusive phantom that we are only able to grasp now and then, and only incompletely. In those moments, consciousness stops the rush of life and puts something together from its chaotic flux.

Existence, in all its emotional resonance and mysterious complexity, resides somewhere in the space between the accumulated bits of experience and the stoppage of thought. We vacillate from one pole to the other, back and forth, ceaselessly. My Struggle is an attempt to embody this process through the eyes of one individual, Karl Ove Knausgaard.

In following his particular way through the rough texture of life, we see what he sees, sometimes in maddening and monotonous detail. And yet we see beyond that as well. For, in staying so true to his technique and in going so far with it, Knausgaard achieves what fiction about the tactile particulars of everyday life should achieve — it illuminates the circuitous path to truth and, in its specificity, it reveals the universal within the singular.3

On October 25, 2014, as part of the International Festival of Authors, Sheila Heti interviewed Karl Ove Knausgaard at the Fleck Dance Theatre here in Toronto. What follows are notes (set down the next day) from that event, detailing some of Karl’s thoughts (to the best of my ability and recollection).

“The Elusive Background Personality” – There was a discussion of the meaning of love. Karl referenced the writing of his wife and the surprise one can find in the thoughts and ideas that emerge from an individual one lives with every day; the unexpected existence of something beyond the regular and habitual. This kind of invisible background personality is something that is almost impossible to articulate. It can only be (unwittingly) discovered and felt in life.

“Eyes Meeting” – Karl mentioned sending a draft of My Struggle to his brother. The subject line of his email response was the somewhat alarming: “Your fucking struggle!” In time, his brother’s response was more measured and understanding. The next time they met, instead of the rare and formal Norwegian handshake greeting, their eyes met. It felt like that was the first time that had happened between them.

“Dragged into Life” – Karl’s wife being more “explosive” (expressive) than him, which is a good counter to his inexpressive nature (which he compared to the surface of a frozen lake). She helps “drag him into life, again and again.”

“The Work of Others” – Karl noted that the experience on his book tour of being able to discover and read the work of more authors. This was a great thing, but he noted (somewhat cryptically) that it is not necessarily a great experience to meet the writers themselves.

“The Untranslated” – Some comments about the challenges of translation and how there is ultimately an unbridgeable gap between an original work and its translation into another language. He noted that there is a wonderfully rich vein of literature in Norway that remains untranslated.

“The Virtual Self and Reality” – Some comments on the splintered nature of our virtual selves in the internet era. Karl noted that there is something more — some beauty, some mystery — in the stuff of everyday physical reality. One has this experience in coming across a painting of simple objects by a great artist; they are expressing something of this ineffable quality in their work.

“The Relation of Writing to Memory” – Karl noted that our memories are structured around larger events in our lives, but the real story is in much that is found between those decisive moments. Those memories are always there in the unconscious, waiting to resurface when we take the time to look at them. The process of writing somehow pulls the reality of those memories out of the depths.

“If It Doesn’t Work, Extend It” – Karl discussed his editor, who has been essential to him for 17 years. Without him, he would not be a writer. He noted that it is the usual procedure, when an editor looks at a manuscript, to tell a writer what needs to be deleted or pared down. Karl’s editor offered a different approach: “If it doesn’t work, extend it, keep going.” Something came out of that. This is largely the basis for the length and detail of My Struggle.

“Complete This Before Doing Something Good” – Karl spoke of My Struggle as a project that he had to keep going on, something to be completed before he could move on to a so-called “great” novel — and the irony that it is My Struggle that has become a celebrated work.

“A Good Parent Disappears” – Karl spoke about the odd fact that he has had difficulty writing about his mother and his wife. With regard to his mother, he noted that, if a parent is good, you don’t quite remember the details of why that is the case. If you have good parents, they disappear from your life.

“Another Space to Inhabit” – To move beyond the reputation of My Struggle involves leaving it behind; stepping away from it and finding another space entirely and inhabiting that space.

“Write What You Have to Write” – One should never approach writing as if it is a “big novel” one is working on. Rather, just write what has to be written.

“Dreams of the Future” – Karl hinted at a possibility for a future novel, something that arose when his editor relayed some of his dreams to him. Karl’s idea was to explore a situation in which an individual dreams of certain events that then happen in the near future. This is an area of interest for him and it is something he may explore further.

Thanks to those who joined me in the #Struggle1 social-read. Most of the discussion of the book took place in this App.net public patter room.

1. The words from Heti, and her book (which I’ve read) both fed into my interest in Knausgaard’s work. Several individuals, in turn, linked to a compelling interview in The Paris Review with Knausgaard; that intrigued me and initiated my interest in reading the book and seeing if others wanted to read it as well. ↩

2. My own comments about the experience can be found in the last paragraph of my final entry on JR. Thanks to Lee Konstantinou and the LA Review of Books (along with the readers who contributed to #OccupyGaddis) for inspiring the structure for this social-read. ↩

3. In the process of setting down these reflections, I came across a few quotes that resonated with the book and my reaction to it. They could not be accommodated in the piece, but I will note them here. One is Nietzsche’s statement (1878) about the goal of his work, that it would seek “small, unpretentious truths found by rigorous methods.” This could describe the approach Knausgaard takes. Also from Nietzsche: “We have art that we may not perish of the truth.” And there is this simple statement from Eduardo Galeano, on the long reach of memory: “The time that was continues to tick inside the time that is.” ↩